(Case Study) Process Reengineering w/ AI

Part 2 of "How I discovered the most valuable AI use case in an F100," a series on AI value in the enterprise

In this letter, you’re going to learn how I led an effort to right-size a project injecting AI into a core business process, which eventually became one of our biggest AI success stories.

As I detailed in Part 1, this was our fastest growing line-of-business. They were having challenges scaling. Without the rapid and strategic injection of AI, their costs would balloon, and they would not be able to deliver to customers with the speed and quality they expected.

This AI workstream already existed, but it was stuttering. The team promised KPI improvements, then fell short of them. “Easy wins” were prioritized over hard-but-impactful investments. It was also severely under-resourced.

I was not told to work on this initiative. But, after thinking through the steps in part 1 (”start with the business”), I realized how valuable this work could be and made it a point to get deeply involved.

At the outset, I knew very little about the business. But by following the steps in this letter, which took ~3 hours of my time split across 2 meetings, I learned enough to help turn this project into one of our biggest internal success stories. So important was the work that it ended up being featured at our big internal strategy conference, which happens only once every 5 years.

You cannot Copilot your way to transformation

To their credit, our senior leaders didn’t just want to say that they were “doing” AI. They wanted AI-driven transformation. More specifically, they wanted a story they could shop around internally and in the marketplace.

Unfortunately, the approach most teams took to finding AI use-cases prioritized obvious, low-hanging fruit. Part of it was teams’ ignorance on what AI could and couldn’t do. Part of it was skittish risk partners, a reality in any enterprise. Part of it was the lack of a structured approach to find valuable use cases.

Market-moving AI stories - the kind that make careers - do not come about by chance. They come about by taking calculated risks. The “calculation” in this case is to find opportunities worth failing at. This was one such opportunity.

Below, you will learn how to:

Take a process engineering approach to find and prioritize AI work, and

Gain the trust of process owners and SMEs so they improve the solution (rather than sabotage it)

Let’s begin.

Quick recap

The first 2 steps I described in Part 1 under the principle “Start with the business” are:

Decide what you won’t do based on your risk tolerance and knowledge

Decide where you will deep-dive based on the size or growth rate of cost or revenue

The next 3 steps, under the principle “Respect the nuance,” are:

Understand current processes and bottlenecks

Brainstorm and prioritize solutions by bottleneck

Use small wins to educate and accelerate

I had originally planned to finish the series today, but it became too long. Today, we’ll go deep into step 3.

Step 3 - Understand current processes and bottlenecks

At this point, most people make one of two mistakes:

They oversimplify the process, then build an unusable solution

They get lost in edge cases and never ship

Balance is key. I achieve this by taking both a quantitative and qualitative approach. The quantitative side is important for finding and justifying process bottlenecks for AI injection. The qualitative side is critical for understanding nuances and edge cases, and also for building positive relationships with SMEs and process owners who are critical for overall success.

I started with the quantitative approach.

3a. Build a process diagram with throughput numbers

It’s amazing how few people will actually go through the trouble of documenting their processes end-to-end. Even fewer will do so with real numbers attached to each step. Both are important for finding opportunities for AI injection and - and this is really key - prioritizing them by impact on business KPIs.

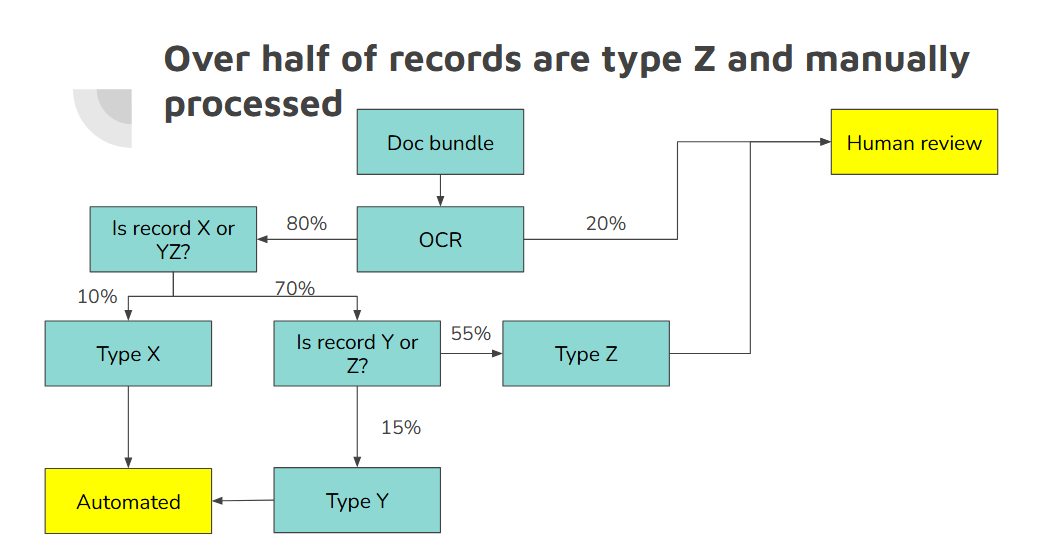

This specific process involved automated document processing. At each step of the automation, a subset of documents was kicked out for human evaluation. The key was to reduce the % of documents that needed to go to humans. This would help the business scale.

Process diagrams help discover bottlenecks. There are 2 kinds of bottlenecks to keep in mind:

Big bottlenecks: Some steps had higher kickout rates than others.

Early bottlenecks: The earlier in the process a bottleneck occurs, the more downstream benefits there are to solving it.

Find out why these bottlenecks exist and why current solutions fail.

I did this exercise in a single 2-hour meeting with a direct report who had a holistic and detailed view of the process. We ended up putting together most of the process diagram. After our session, they spent a couple more hours querying data to fill in the throughput numbers in between the steps (see mockup below). If you don’t have a single process owner or expert, this will take longer.

We fit this process diagram onto a single slide. This slide broke all the “rules” of slidecraft. The text was small enough that you needed to zoom in to read it. There were lots of numbers. There wasn’t even a key for the colors we used. It didn’t matter. This became the most widely shared, discussed, and valuable slide I’ve ever worked on. An SVP remembered specific numbers from it 3 months after I first showed them our work.

That’s the power of a process-oriented approach. You clarify your thinking, discover opportunities, and create shareable artifacts to get others’ buy-in - all at the same time.

Here’s a highly oversimplified slide mockup of what a basic process diagram with throughput numbers might look like:

This diagram would suggest focusing on processing Type Z records, the biggest bottleneck. It would also suggest improving OCR, the earliest bottleneck, which is also fairly sizeable. Improving OCR could improve automation numbers by increasing the number of Type X and Y records downstream, both of which can be processed automatically.

If you want to learn more about the thinking behind this, look into “Business Process Reengineering.”

Process diagrams are great decision-making artifacts, but they are not enough. They often fail to capture the subtle nuances and human judgments relevant to a process.

That’s why we need the next step: qualitative research.

3b. Job shadow the experts (and take lots of notes)

The more in love you are with technology, the more you will ignore this. I’ve seen it many times, especially when consultants are brought in to revamp a process. Pressured to deliver quickly, and, lacking skin in the game, they cut corners and build something unusable. Nothing creates change fatigue faster than solutions that fail to solve real problems.

Nuance matters, especially from a risk perspective. “Requirements gathering” is not enough, because people don’t know what they want, and some knowledge is so implicit that they won’t even think to tell you. You must become an expert at observation.

This is where qualitative research comes in.

There are many ways to do it. On the shallow end are interviews, where people tell you what you think to ask for. On the deep end is participant-observation fieldwork, where you may spend months or years in the field living with people and participating intimately in their lives. (I was an anthropology major and have deep respect for all ethnographic research that comes out of participant-observation methods.)

Job shadowing is a nice middle ground. It’s time efficient while making room for nuance. Critically, you can see what people do and not just rely on what they tell you.

I only spent an hour job shadowing. I found the #1 SME on the manual process and setup a meeting with them and several folks from our side. Then,

The SME opened real documents and start to talk through their thought process.

I took notes furiously and asked lots of questions.

I paid special attention to dependencies and edge cases.

When steps came up that overlapped with the big and/or early bottlenecks I identified earlier, I went deeper. “What’s so hard about automating these steps? What do experts know that machines don’t? Does the data needed to do this live anywhere, or is it just in peoples’ heads?”

If you want to learn more about the thinking behind this, look into user experience, customer experience, and ethnographic research.

Strategic AI injection requires an end-to-end view

I had what I needed - a holistic view of

how experts do the process, and

how we already automate (some) of the process

I generated these insights with less than a single business day’s worth of work.

This is neither the out-of-the-box approach to AI often taken by non-experts, nor the haphazard and complexifying resume-driven-development often done by technical specialists.

This is how you start to think of solutions - AI or otherwise - in a strategic manner.

In other words:

Do not focus on “easy.”

Do not focus on “cool.”

Focus on impact.

You might think it ironic that you need this level of tactical detail to make the most “strategic,” leveraged and defensible AI investments. But if, as they say, the devil is in the details, consider this permission to go full-on demon.

But before you start brainstorming solutions to the bottlenecks you so painstakingly found, I must address the elephant in the room.

What if the SMEs and process owners don’t trust me?

You won’t make this work if SMEs won’t work with you.

This is quite common. They might think you’re trying to automate them out of a job. They might not trust that an automated system could replace them. Maybe your team or organization made big promises in the past and failed to deliver, and they just don’t trust you.

The first thing you should do is acknowledge to yourself that they might be right.

Maybe you are trying to automate them out of a job. Maybe an automated system could never replace them. Maybe your team did fail to deliver in the past. I’ve noticed that because enterprises spend a lot of time and energy chasing fads, teams become jaded and develop change fatigue.

You may not be able to control all these factors, especially the structural incentives. This is one of the reasons I chose to work with a line-of-business that was growing quickly, rather than an older organization looking to cut headcount.

That said, if you are facing these challenges, what can you do about it?

Start with transparency

Start by being transparent and coming clean. They say “bad news compounds”; resentment and distrust are no different. Acknowledge anything that might have gone wrong in the past, and be specific about how things will be different in the future. Work with more cooperative individuals to cocreate a vision for what their work will look like after the transformation. This kind of work is mostly done 1:1, before project kickoff in a group setting.

Not everyone is suited to this kind of relationship-building and repair. It’s certainly not always the highest-ranked person in the room. In fact, many senior leaders become, over the years, quite disconnected from the day-to-day realities of the front-line. Over time, they lose respect for details and become accustomed to getting things done through their rank. This will never build trust.

Show “equal opportunity respect”

You need someone with an abundance of curiosity and genuine respect and empathy for the other side.

Job shadowing was one way I showed curiosity and respect. I made very clear that I wanted to understand the nuance behind what they do so we could build something that would work. I also told the SME that they were widely acknowledged by everyone as the top expert in this process, which was true, and also probably made them feel respected and acknowledged.

Safi Bahcall makes this point rather beautifully in his book Loonshots, in a far more high-stakes context.

Some context: Vannevar Bush ran the U.S. Office of Scientific Research and Development from 1941-1947, which conducted almost all U.S. military R&D during WWII. While many today take for granted the strong link between science and the military, it was not always so. Bush succeeded where many before him failed in getting the military to actually use new and “unproven” technologies developed in the lab.

As Safi describes,

Equal-opportunity respect is a rare and valuable skill. Vannevar Bush, although a veteran academic at the start of the war, genuinely respected the military. “I have enjoyed associating with military men more than with any other group, scientists, businessmen, professors,” he wrote years later. The deference with which Bush treated officers helped him understand, and ultimately influence, the military far more than the many scientists and engineers who had tried, and failed, before him.

If you can embody “equal opportunity respect,” the rest will follow.

Thanks for reading. Next part of this case study comes out next week!